“A Providential accident”: Nova Scotia in Thomas Merton’s The Waters of Siloe

- Colby Gaudet

- Jul 15, 2025

- 15 min read

Updated: Nov 13, 2025

In the late 1940s, Thomas Merton, the well-known Trappist monk, composed a history of his religious order. In this work, titled The Waters of Siloe, Merton devoted a chapter to Nova Scotia, telling the Trappists’ distinct nineteenth-century episode in the province, beginning with a refugee monk stranded in Halifax in the summer of 1815. This monk – born Jacques Merle in France in 1768 – was known by his devotional name, Father Vincent de Paul (after the seventeenth-century French reformer and saint). Vincent had been among a cohort of French Trappists sent to the United States in 1813 to establish Roman Catholic monasteries in Maryland, Kentucky, and Illinois.[1] Failing to do so after two years due to a lack of support and resources, the Trappist abbot, Augustin de Lestrange, instructed the monks to cease their efforts and summoned Vincent and his colleagues to regroup in New York City before returning to Europe. During a stopover in the port of Halifax on the return voyage, Vincent missed his vessel’s departure – perhaps intentionally so he might continue his personal mission in North America.[2] Hearing of Vincent’s situation, Bishop Plessis and Governor Sherbrooke each supported a decision to keep the stranded monk in Nova Scotia where there was a great need for Catholic clerics.[3] And permission to stay was requested of Lestrange who, in the end, acquiesced. The near fifty-year-old Father Vincent thus remained in the British colonial province, where, for the next several decades, he would have a significant impact on local communities.

After working intermittently as a parish priest in eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton, by the 1820s Vincent began executing his larger vision: to establish an agricultural monastery with a group of fellow Trappists recruited from France. In The Waters of Siloe, Merton positions this rustic monastery – known as Petit Clairvaux near the village of Tracadie – as an experimental, but ultimately failed, precursor to the later success of his own resident monastery – Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky, established by French Trappists in 1848 (and where Merton lived in the 1940s). Despite Merton’s dismissal of Clairvaux, he recognized its contribution to the development of Trappist foundations in North America. Beyond Merton’s sometimes cursory treatment (itself based on Trappist manuscripts), and within the regional purview of Atlantic Canadian history, the Trappists’ Nova Scotian episode reveals compelling contours of Maritime Catholic history at a time when no comparable religious communities existed in the province. The Trappist episode also contributes to historical knowledge of the Acadians and Mi’kmaq – Vincent’s target communities.[4]

The Trappists (named for La Trappe, their first abbey) are a contemplative order, founded in France in the seventeenth century and derived from the Cistercian tradition. During the anti-clericalism of the French Revolution, the Trappists fled to Switzerland until Lestrange decided to send a group of monks to North America. Merton described the Trappists’ first effort at establishing monastic roots in the United States as a “strange story” that, by the time of their New York rendezvous in 1815, “was not quite ended.” In fact, the refugee monks’ “strangest episode was just about to begin. By a Providential accident, the congregation maintained a more or less theoretical foothold in the New World.” For it was the stranded Vincent who – as “the last survivor” of the American expedition – “was able to make a foundation in Nova Scotia.” Strong willed and independently minded, Vincent, sequestered in Halifax and isolated from his religious brothers, “was not completely shattered by this accident … so that many people in the Order have accused him of getting stranded in Nova Scotia on purpose.”[5] This “accident” and Vincent’s “foothold” would set in motion later events of consequence to both the fate of the Trappists in North America, and, on a regional scale, to pre-Confederation Nova Scotia. Amid the province’s dearth of Catholic clerics, and with several settler and Indigenous Catholic communities in need of pastoral care, Vincent was put to work in his new home.

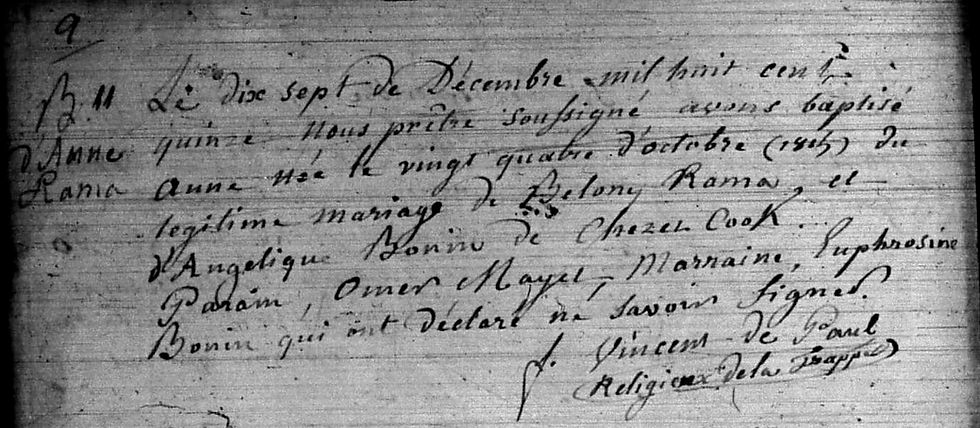

According to Merton, perhaps it was the holy will of God “that had placed him [Vincent] in this land, which was almost destitute of priests; where there were numerous colonies of French Catholics [Acadians] and scores of settlements full of Micmac Indians who had once received the faith from missionaries, but who had now been without priests for fifty years [since the Seven Years’ War].”[6] As there were only two other Catholic priests in the provincial capital, Vincent performed parish duties at Chezzetcook, a coastal Acadian village to the east of Halifax. Merton described Vincent’s first year of ministry, and included a brief yet compelling detail concerning the monk’s non-white companions (quiet likely servants, but perhaps also having personal histories of enslavement). “When the winter of 1815 set in, Father Vincent, wearing his white Cistercian cowl and accompanied by three mysterious Negroes who had followed the monks from New York, entered the little village of Chezzetcook, where he settled down to two years of parish life.”[7] The sight of such a distinct troupe as a monk dressed in white monastic robes muddied with travel, accompanied by three African Americans, would have cast a curious aura in the rural village. Merton provided no further details about the identities of Vincent’s companions – they were evidently mentioned in the Trappist manuscript Merton consulted. That Merton wrote they "followed" Vincent undercuts any notion that these three individuals (men or women, we don't know) were bound to the Trappists in some way, as servants or slaves. And the Acadians of Chezzetcook would have had wider social contact with people of African descent as their settlement was near the village of Preston, established for Black Loyalists in the 1780s and inhabited by many Black refugees of the War of 1812. From Chezzetcook’s surviving parish register, Vincent’s signature can be read on a number of Acadian baptismal acts dating to 1815 and 1816. He signed the register as “Vincent de Paul, Religieux de la Trappe”.[8]

After a few years at Chezzetcook with the Acadians, Vincent relocated and worked more actively with Indigenous communities in eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton. Giving no context to Nova Scotia’s colonial history, Merton romanticized Christian mission work while also emphasizing Vincent’s saintly hardships.

[T]here was much to keep him busy. Long canoe voyages over treacherous waters,

and tramps through the woods with an Indian guide brought him to outlying

Micmac villages, where he preached and administered the Sacraments and taught catechism all day. At night he slept on a bed of branches, under a bearskin, while

the rain came through the roof or the walls of the hut. It would have taken courage

for a strong man to do all this: but Father Vincent’s health was not good. To add

to the laborious life, he was having trouble learning the Indians’ language.[9]

Despite Vincent’s personal zeal, this range of intrepid missionary activity was odd behavior for a monk of a contemplative order who would have otherwise lived an intentionally quiet, rooted, and routine existence. In contrast to Vincent’s training for a life of contemplation, Merton stated, “[t]he active ministry was in his blood. And this influenced his whole conception of the Trappist vocation.” Vincent’s social and physical isolation in rural Nova Scotia compelled him to be very active, necessarily travelling about, writing letters, and meeting with people in the secular world. All with the hopes of establishing and funding his monastery. “Unfortunately,” observed Merton, “the promised foundation was slow in materializing. The British government made no show of giving official permission [for such a Catholic institution in a Protestant empire],” and Lestrange, “far from offering any help, did not even answer Father Vincent’s letters.”[10]

In the spring of 1818, Vincent took matters into his own hands and “made a two-hundred-mile tour of Cape Breton and Antigonish” during which “he discovered a piece of property that suited him. It was a wooded valley half a mile from the sea, near a settlement called Big Tracadie.” Vincent planned to execute his mission to the Mi’kmaq through the agricultural and educational model of the monastery he would build on this land.[11] “[T]he Trappist pioneer bought these three hundred acres and put down on paper his notes on the projected Indian village, complete with school, workshops, farmlands, cooperative store, and so on.”[12] It would be a number of years before Vincent could obtain any material support to commence construction of his monastery, but the desired location was found and the land purchased.

In the meantime, Vincent included in his vision for the Clairvaux monastery a convent of Trappist nuns – called Trappistines. The monk’s activities thus had a notable significance for the region’s Acadians as these future nuns would come from the local parishes – parishes whose women had no previous educational opportunities. In 1822, Vincent sent “three solid, healthy Acadian girls up the river to Montreal to make their noviceship in a convent of teaching sisters [the Congrégation de Notre Dame]. After this, they would take vows as ‘Trappistines.’” While Merton did not name these three young Acadian women, research I’ve conducted at the Nova Scotia Archives has located copies of Vincent’s letters to the Superior of the Congrégation de Notre Dame. These letters identify the three Acadian novices: Anne Côté (age 24), Marie Landry (18), and Olive Doiron (25).[13] Until this novel undertaking, young Acadian women in Nova Scotia would have had little to no access to francophone convent schools in Lower Canada, and no such institutions yet existed in the Maritimes. Vincent’s organizational and administrative presence thus facilitated the development of religious vocations for some Acadian women.[14]

When Lestrange finally replied to Vincent’s proposals for Clairvaux, the abbot discouragingly told the monk that despite his efforts, “it was useless to start a foundation in Nova Scotia.” Instead, Lestrange suggested Vincent return to the United States with a renewed mission. After all, “Bishop Flaget of Bardstown was still anxious to have Trappists in Kentucky.” For Vincent, “going to Kentucky seemed out of the question,” and, in October 1823, he returned to France to speak personally with Lestrange about his desire to remain in Nova Scotia.[15] Hearing of the progress at Clairvaux, the abbot accepted Vincent’s plan and permitted him to recruit Trappist brothers to accompany him to Tracadie. “They would be six in all,” including Francis Xavier, “a survivor of the Kentucky mission.”[16] In 1825, Vincent brought his fellow Trappists to Tracadie and requested of Nova Scotia’s lieutenant governor “permission d’exister en corps de Communauté sur les terres de sa dépendance.” In this petition, Vincent outlined his goals to assimilate the Mi’kmaq as colonial subjects. At Clairvaux he would “réunir en village, s’il est possible, les Micmacks autour ou près de l’etablissement projetté, afin d’être plus à la portée de les instruire, de leur apprendre à cultiver la terre, les arts et métiers.” Typical of colonial attitudes of the time, such instruction for Mi’kmaq was deemed necessary as Vincent was “pérsuadé que tant qu’ils seroit errants et vagabonds, on ne pourra jamais bien les civiliser.”[17] With these remarks, Vincent expressed a similar vision for Christianizing Indigenous people as did many missionary figures in the nineteenth century. In the eyes of Catholic clerics such as Vincent or Plessis, it was necessary to complement a Christian life for the Mi’kmaq with formal schooling and training in agriculture. That way, Indigenous people could be taught to adopt Western ways and leave Indigenous culture behind as artefacts of history.[18] To execute his plan of ‘civilizing’ the Mi’kmaq, Vincent was granted £50 in 1826 by the Nova Scotia government for “educating and taking care of such Indians.” Yet, he struggled to receive continued support for completing his industrial vision for the monastery. In 1830 and 1832 he petitioned for “aid towards the completion of a Mill for grinding Oats and dressing Barley, at Tracadie.”[19]

With these developments, Petit Clairvaux was underway from humble beginnings. In Merton’s words, the Trappists “settled in a little wooden building near the site Father Vincent had chosen five years before at Big Tracadie and began their official existence in the usual desperate poverty. They had no money, paying for commodities with potatoes, cabbage, and beef. The monks taught school, and the three sturdy Acadian girls who had gone to the novitiate in Montreal were summoned to Tracadie, dressed in habits, and placed in a little wooden house.”[20] In 1836, Vincent again traveled to France to recruit more monks. After his return to Nova Scotia several years later, he remained at Tracadie until his death in 1853. Clairvaux then came under the direction of Vincent’s confrere Francis Xavier until 1857 with the arrival of Belgian Trappists who operated the monastery until 1919 at which point it closed for several years before being taken over by Augustinians.

In Merton’s final review, “it is almost incredible that Petit Clairvaux lasted as long as it did.” Despite its struggles, Vincent’s Nova Scotian monastery had a marked impact on the history of Trappist reforms – it laid bare the incongruence between the contemplative monasticism of the Trappists’ Cistercian origins and the agricultural-industrial model developed by more recent Trappist reformers. For Merton, Clairvaux demonstrated that the active life of farming, manufacture, and schooling drew the monks away from the contemplative, prayer-oriented life of their order’s roots. This tension that had developed internally within the Trappist model “lay fully exposed to view in the dry bones of what was called Petit Clairvaux.”[21] As a Trappist himself, Merton’s conclusions about Clairvaux reflect his concern for Trappist history, its successes and failures. For specialists in Atlantic Canadian history, Merton’s inquiry (and Vincent's career) can also be a bridge to expanding scholarship on the Acadians and Mi’kmaq. For instance, as with the examples of Anne Côté, Marie Landry, and Olive Doiron, close attention to the history of Clairvaux’s Trappistines could contribute to Maritime women’s history and shed greater light on the underanalyzed history of Acadian women’s religious vocations.[22]

In his study of colonial policies concerning the Mi’kmaq, historian Leslie Upton had some of the same critiques of Vincent as did Merton, pointing out that Vincent “lost even the moral support of his own order, presumably because his missionary zeal violated the contemplative life to which Trappists were bound.” On Vincent’s work with the Mi’kmaq overall, Upton was dismissive, yet acknowledged: “He maintained his contacts with the Indians over the years and had their respect.” In the long term of Vincent’s mission, “[h]e changed their lives not one iota.”[23] Such an outright dismissal seems premature.

As Clairvaux expanded in the nineteenth century, its work focused less and less on Indigenous people, and the rocky administration of the monastery seems to have led Upton to doubt its long-term influence. Still, with continued research, evidence of Vincent’s impacts on individual Mi’kmaq might emerge, especially considering the greater understanding of the historical links between Catholic missions, industrial schools, and residential schools that has arisen since the time of Upton’s writing. For instance, in his 1843 “Report on Indian Affairs,” Joseph Howe noted the impression a particular Mi’kmaw man had made upon him during a recent tour of the province. “I have been much interested with two Indians during the past year.” One, a shoemaker, living near Windsor. “Another, Michel, a youth reared and educated by Pere Vincent, at Tracadie, appeared very intelligent and ingenious – he spoke English, French and Micmac fluently, was an excellent Carpenter and Turner, and had built the waggon in which the Pere and himself rode to town.”[24] As Michel’s example suggests, Vincent’s career merits further study to better elucidate the monk’s educational project locally and his possible contributions to the overall church-state development of day schools for Indigenous children in Mi’kma’ki and Wolastoqey.

Whether Vincent’s lingering presence in Halifax in the summer of 1815 was a ‘providential accident’ or a result of willful self-determination, his committed presence in Nova Scotia for the following three and a half decades had impacts beyond the interests of the Trappists alone. On balance, Merton's chapter positions Nova Scotia as a 'strange', vital, and innovative testing ground in the global, nineteenth-century scope of his order's endeavours. The Waters of Siloe is a worthwhile read not only for Merton enthusiasts. It's a valuable text for specialists in Atlantic Canada as it contributes to the region's history of religion, empire, and colonialism, with particular potential for histories of women and Indigenous people.

[1] Lawrence Francis Flick, “The French Refugee Trappists in the United States,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia 1 (1884–1886): 86–116.

[2] Paulette Chiasson, “Merle, Jacques, named Father Vincent de Paul,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography online, v. 8, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/merle_jacques_8E.html. For a translation of Vincent’s memoir, see A.M. Pope, trans., Memoir of Father Vincent de Paul, Religious of La Trappe (Charlottetown, PE: John Coombs, 1886).

[3] When Plessis heard of Vincent’s presence in Halifax he wasted no time in proposing to Sherbrooke a plan for a Trappist agricultural monastery in Nova Scotia, see Joseph-Octave Plessis to John Coape Sherbrooke, 27 July 1815, Nova Scotia Archives (NSA), RG-1, v. 430, no. 153; and Plessis to Sherbrooke, 4 August 1815, NSA, RG-1, v. 430, no. 154. Plessis' proposal was especially focused on 'civilizing' the Mi'kmaq. Such a plan would not actualize for more than a decade. Plessis, who happened to also be in Halifax in the summer of 1815 during a pastoral tour, recounted his own version of the Trappists' voyage to the United States and the circumstances leading to Vincent's presence in Halifax. See Joseph-Octave Plessis, “Le journal des visites pastorales en Acadie de Mgr Joseph-Octave Plessis: 1811, 1812, 1815,” Les Cahiers de la Société historique acadienne 11, nos. 1, 2, 3 (March- September 1980): 181–186.

[4] On Clairvaux, see Ephrem Boudreau, “Le Petit Clairvaux (1825–1919),” Les Cahiers de la Société historique acadienne 7, no. 3 (September 1976): 131–146; Luke Schrepfer, Pioneer Monks in Nova Scotia (Diocese of Antigonish, 1947), 16–66; A.M. Kinnear, “The Trappist Monks at Tracadie, Nova Scotia,” Report of the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Historical Association 9, no. 1 (1930): 97–105. Vincent and Clairvaux are discussed throughout A.A. Johnston’s A History of the Catholic Church in Eastern Nova Scotia, vols. 1 and 2 (Antigonish: St. Francis Xavier University Press, 1960 and 1971). On the overall Catholic context of the Maritimes, see Terrence Murphy, “The Emergence of Maritime Catholicism, 1781–1830,” Acadiensis 13, no. 2 (Spring 1984): 29–49. My own familiarity with Merton comes from my time as a master’s student at the Vancouver School of Theology with its Thomas Merton Reading Room and annual summer seminar about Merton. Only recently have I read The Waters of Siloe and made the connection between Merton’s Trappist historiography and colonial Nova Scotia. Certainly, Merton is not known as a historian, and many Merton enthusiasts dismiss Waters as the author’s most anomalous and least relevant work – a historical project of little interest to modern seekers drawn to Merton for his spiritual direction and insights on comparative religion and social justice. And Merton’s research and citational methods leave much to be desired in a historian’s eyes. The charismatic monk is better known for his literary merits, including his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain (1948), and his collection of essays, Mystics and Zen Masters (1963). On Merton’s historiographic efforts, see Mary Murray, “The Waters of Siloe as Literature: Thomas Merton Glad to be Home in the Cistercian Order,” The Merton Seasonal 21, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 4–7; Louis Lekai, “Thomas Merton: The Historian?” Cistercian Studies 13, no. 4 (1978): 384–389.

[5] Thomas Merton, The Waters of Siloe (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1949), 83–84.

[6] Merton, Waters, 84. Merton’s passing language of “numerous colonies” and “scores of settlements” suggests the superficial nature of his knowledge of the social and demographic conditions of Acadians and Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia at this time.

[7] Merton, Waters, 88. On Chezzetcook, see Ronald Labelle, "La vie acadienne à Chezzetcook," Les Cahiers de la Société historique acadienne 22, nos. 2-3 (1991): 11–95.

[8] Registre des Baptemes, des Mariages et des Sépultures faites dans la Paroisse de Chezzetcooke, NSA, reel 11,287. In the context of early twentieth-century US Catholic historiography, David Endres has observed a similar tendency to obscure and "deemphasize" the historical reality of slavery. When Catholic clerics traveled to new mission locations, enslaved workers were often described in early histories as 'accompanying' (rather than being owned by) the missionaries, see Endres, "Contending with a Slaveholding Past: Slavery and U.S. Catholic Historiography," in Slavery and the Catholic Church in the United States: Historical Studies, ed. Endres (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2023), 246.

[9] Merton, Waters, 88.

[10] Merton, Waters, 87–88.

[11] Such projects were typical of the Trappists globally at this time, see Jay Butler, “Agricultural Missionaries: The Trappists and French Colonial Policy under the July Monarchy,” The Catholic Historical Review 106, no. 2 (Spring 2020): 256–281. Big Tracadie was also a location of early Black settlement in Nova Scotia, as it was near Guysborough, where many Black Loyalists were brought following the American Revolution. For the history of Black families in Big Tracadie, see Les Rose, Seven Shades of Pale (National Film Board, 1975), https://www.nfb.ca/film/seven-shades-of-pale/.

[12] Merton, Waters, 88–89. Merton is here referring to Vincent’s “Plan d’organization pour un établissement de Sauvages,” NSA, MG-100, v. 239, no. 22A, p. 4. This document is a copy made in 1929 from the Trappist archives of the Abbaye Notre-Dame in Oka, Quebec. Vincent purchased this land at Tracadie from two Acadian families in December 1820 (deeds registered August 1826), see Louis Petitpas and Casimir Benoit to “Reverend Father James Vincent,” NSA, Antigonish County Registry of Deeds, Land Transactions Register, Book 6, 137–141.

[13] Merton, Waters, 90. See Vincent de Paul to Marie-Victoire Beaudry (Sœur de la Croix), 4 June 1822, NSA, MG-100, v. 239, no. 22.

[14] Communities of Catholic women religious would be established in urban centres such as Halifax in the late 1840s, and among the rural Acadians of southwestern Nova Scotia in the 1860s, see Mary Olga McKenna, “An Educational Odyssey: The Sisters of Charity of Halifax,” in Changing Habits: Women’s Religious Orders in Canada, ed. Elizabeth Smyth (Ottawa: Novalis, 2007), 69–85. The history of nuns at Tracadie, NS, is not to be confused with the history of nuns at Tracadie, NB, see Laurie Stanley, “‘So Many Crosses to Bear’: The Religious Hospitallers of St Joseph and the Tracadie Leper Hospital, 1868–1910,” in Changing Roles of Women within the Christian Church in Canada, eds. Elizabeth Muir and Marilyn Whiteley (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), 19–37.

[15] Merton, Waters, 90.

[16] Merton, Waters, 92.

[17] Vincent de Paul to James Kempt, 6 November 1825, NSA, RG-1, v. 232, no. 41.

[18] For a broader discussion, see Kathryn Gin Lum, Heathen: Religion and Race in American History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2022).

[19] Journal and Proceedings of the House of Assembly of the Province of Nova Scotia (1826), 642; Journal and Proceedings (1830), 605; Petition of Revd Pere Vincent of Tracadie, 25 January 1832, NSA, RG-5, Series P, v. 51, no. 109.

[20] Merton, Waters, 93.

[21] Merton, Waters, 93–94. Butler, in “Agricultural Missionaries”, examines similar tensions between the Trappists’ religious worldview and the secular forces to which they found themselves subject in nineteenth-century Algeria and Martinique.

[22] For one such study, see Robert Pichette, Les religieuses, pionnières en Acadie (Moncton: Michel Henry, 1990). Also, Brenda Dunn, “Aspects of Lives of Women in Ancienne Acadie,” and Sally Ross, “Rebuilding a Society: The Challenges Faced by the Acadian Minority in Nova Scotia During the First Century After the Deportation, 1764–1867,” in Looking into Acadie: Three Illustrated Studies, ed. Margaret Conrad (Halifax: Nova Scotia Museum, 2000): 29–80.

[23] L.F.S. Upton, Micmacs and Colonists: Indian-White Relations in the Maritimes, 1713–1867 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1979), 159.

[24] Journal and Proceedings (1844), Appendix 50, 126.

Comments